"Hurrah, We'll Retrocede!"

/When I first moved to Washington, DC, I wondered why it is shaped the way it is. When I moved to Alexandria a few years later, I learned that Alexandria and Arlington County are part of the reason why.

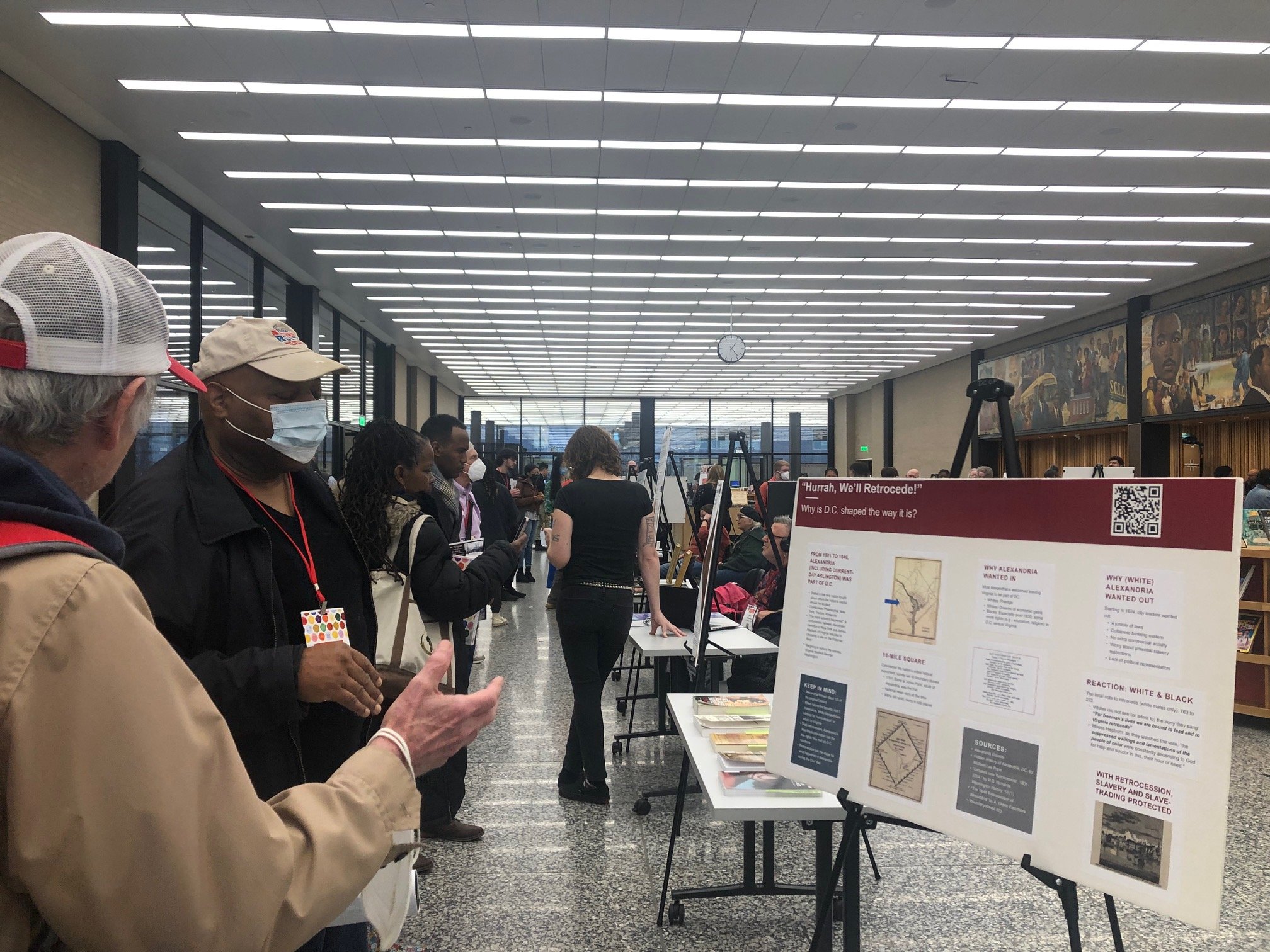

I decided that Retrocession—in which Alexandria “retroceded” back to Virginia from the District in 1846—would be a good topic to propose for a poster at the recent D.C. History Conference.

More of a Deal than I Expected

I could blame it on COVID and the fact that I have not attended in-person conferences for a while. Or that I got busy with other things and did not really focus on the “poster” part of “poster session.” Whatever the reason, early last week, I received an email from the organizer with the specs and saw a photo of a poster session from an earlier conference.

Dang! Those posters looked good.

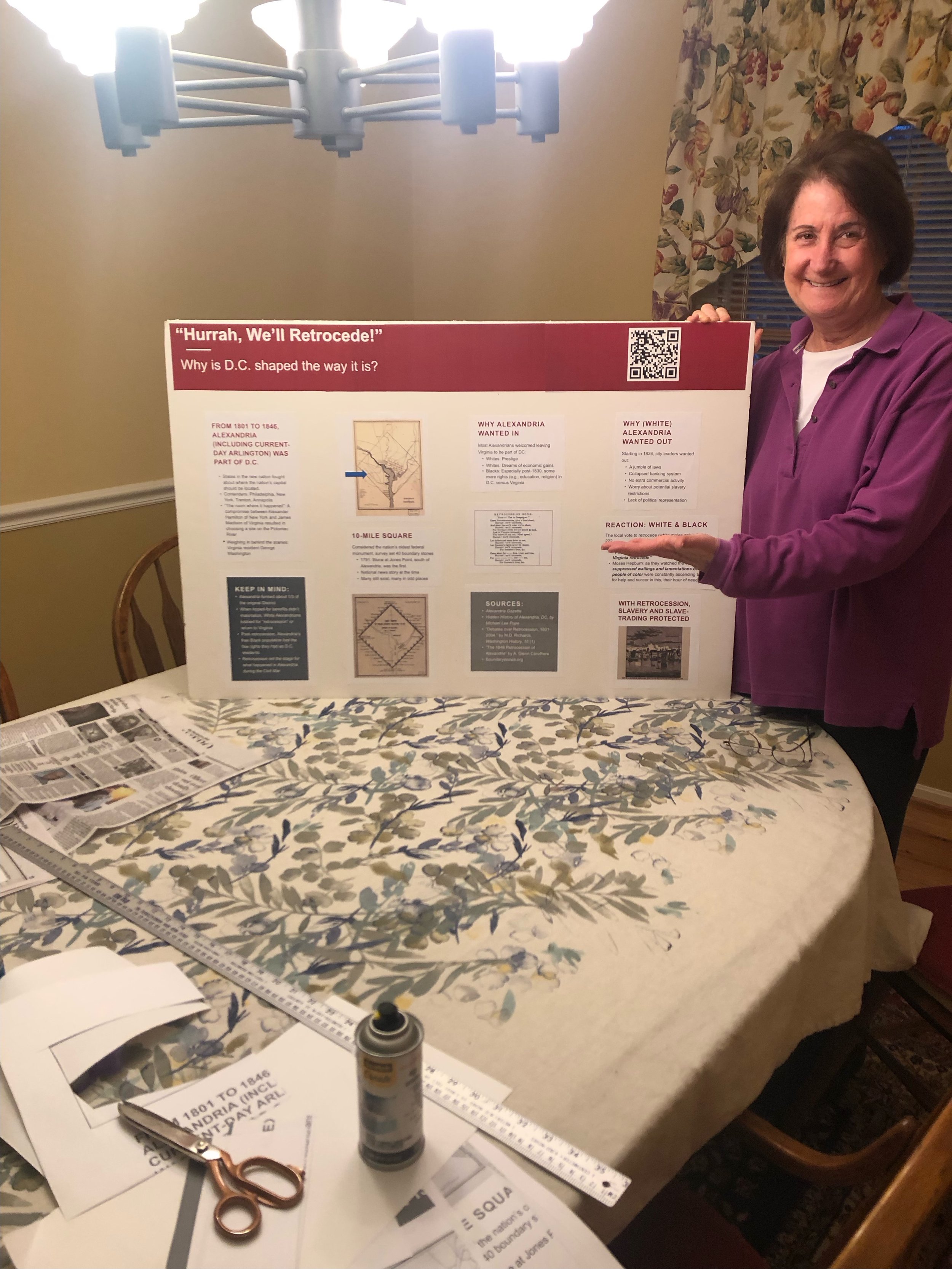

Fortunately, my friend Beth had information about posters from her work at the University of Washington. She sent a few links, including a template to use in PowerPoint. I found a trifold display board that my son and a friend had used for a middle school science fair. I stripped off the description of their experiment. (It involved inserting a seed into a tulip bulb to see how both grew; hopefully, I did wantonly destroy a scientific breakthrough.) Instead of the floppy cardboard that I planned to use, I had a firm 2’ by 3’ piece of foamcore.

The main advice was to pose only question and not use too many words to answer it. I laid out my question—Why is D.C. shaped the way it is?

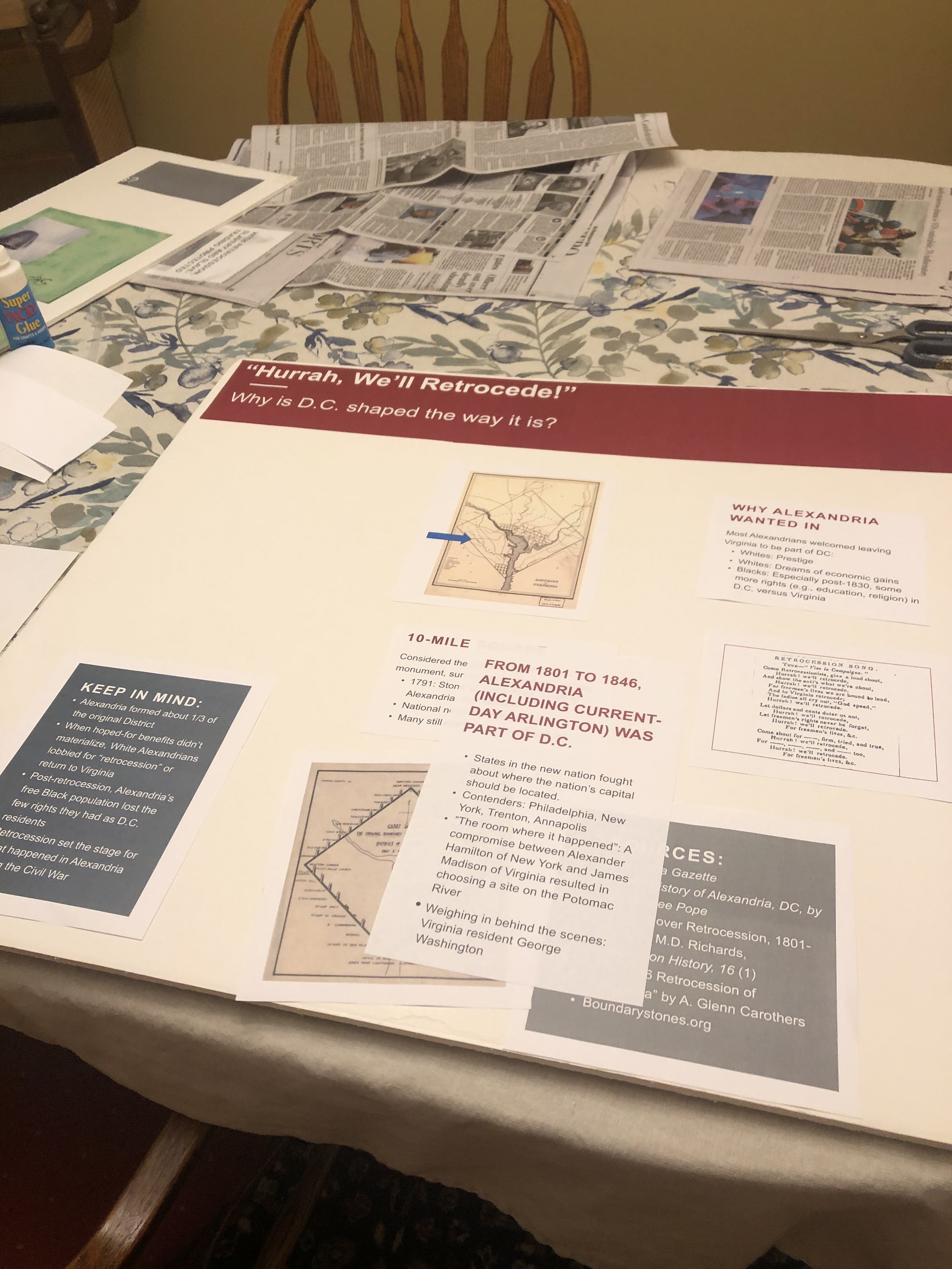

Then I used the template to create blocks of text and images. By Thursday, it looked pretty good on my screen.

Step one accomplished

Only one problem—how to print it super-large? I could have sent it to Staples, but I didn’t want to spend the money for one-time use or deal with sending something and finding something to fix. Besides, as you may have gathered, I waited until the last minute.

My husband found a way to “tile” sections of the whole to print. We tried this many times in black-and-white. The problem was weird text and picture breaks that we couldn’t seamlessly close up. The craft glue in a drawer in the basement clumped. Friday afternoon, the breakthrough inspiration was to position each block on its own piece of paper. A trip to a craft store revealed a whole new world of glues. Spraymount adhesive is my new friend. We assembled the piece on the dining room table Friday night.

Miraculously, on Saturday morning, it was still in one piece. Unfortunately, it was also raining. Two garbage bags protected it before the Big Reveal.

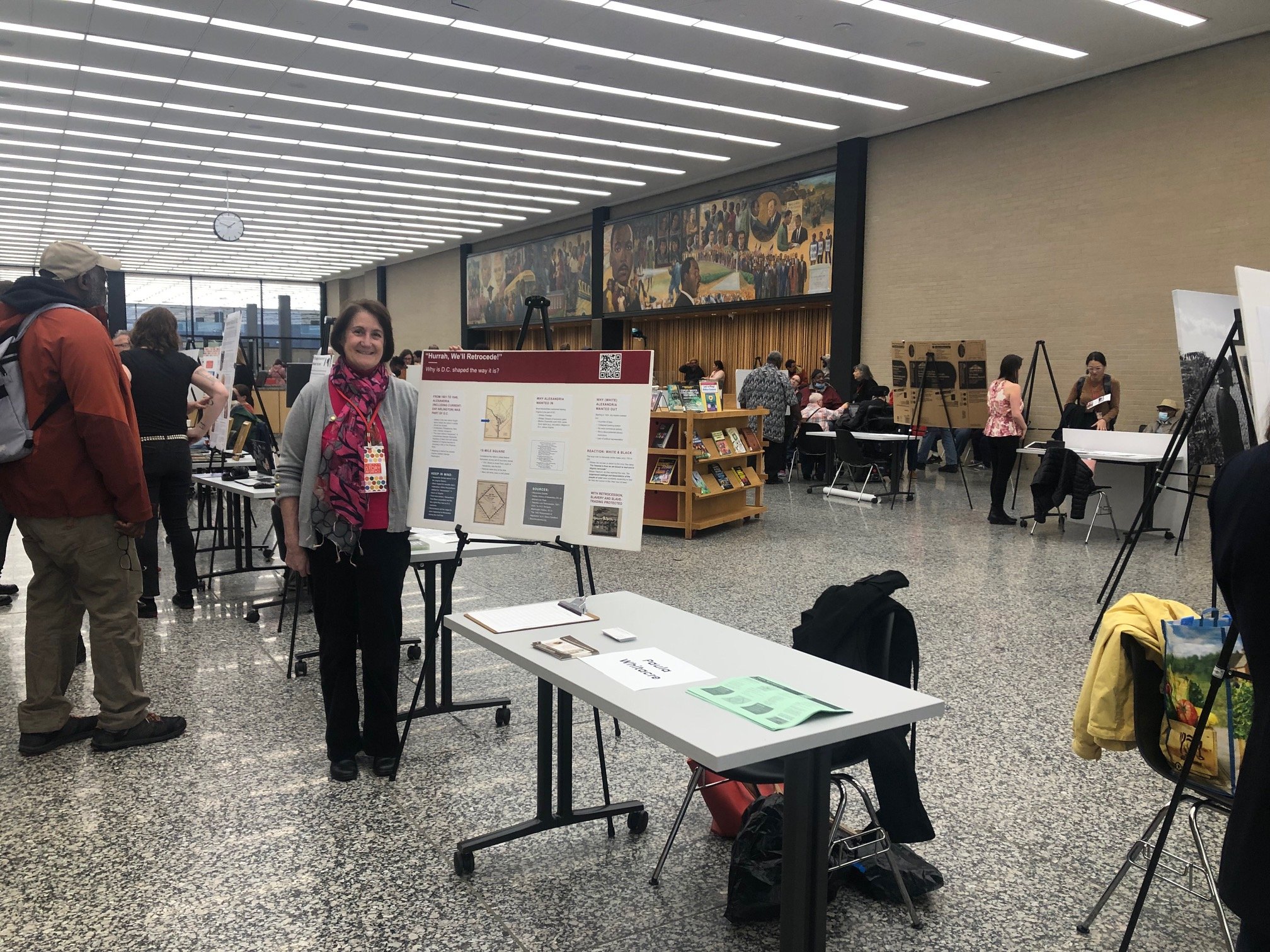

After all this, would anyone even show up to see my poster? Most of the conference took place on the library’s fourth floor, but the poster session was on the first floor. Would attendees come down?

Yes! And so did many other visitors to the library. (Maybe the rainy day brought more people indoors.) The result was a really fun two hours talking with some people who knew more about retrocession than I did, some people who had never heard of it, and many people in between.

And Now: The Content

Alexandria (which encompassed the current city and Arlington as Alexandria County) was part of the District of Columbia from 1801 to 184g, when it “retroceded” to Virginia.

For those like me who need a refresher, several states wanted to host the capital of the new nation. Prestige and money was at stake. While the wheeling-and-dealing for a permanent capital took place and then during construction, short-term solutions included Philadelphia, New York, and Annapolis.

Southern politicians, especially Virginians like Thomas Jefferson pushed for a capital further south. Virginia resident George Washington added pressure to consider the area around the Potomac. Washington, a surveyor, saw the region as “the gateway to the interior.” It didn’t hurt that the location would benefit his plantation at Mount Vernon and other business dealings. Debate stalled until a deal between Alexander Hamilton from New York and James Madison of Virginia was reached.

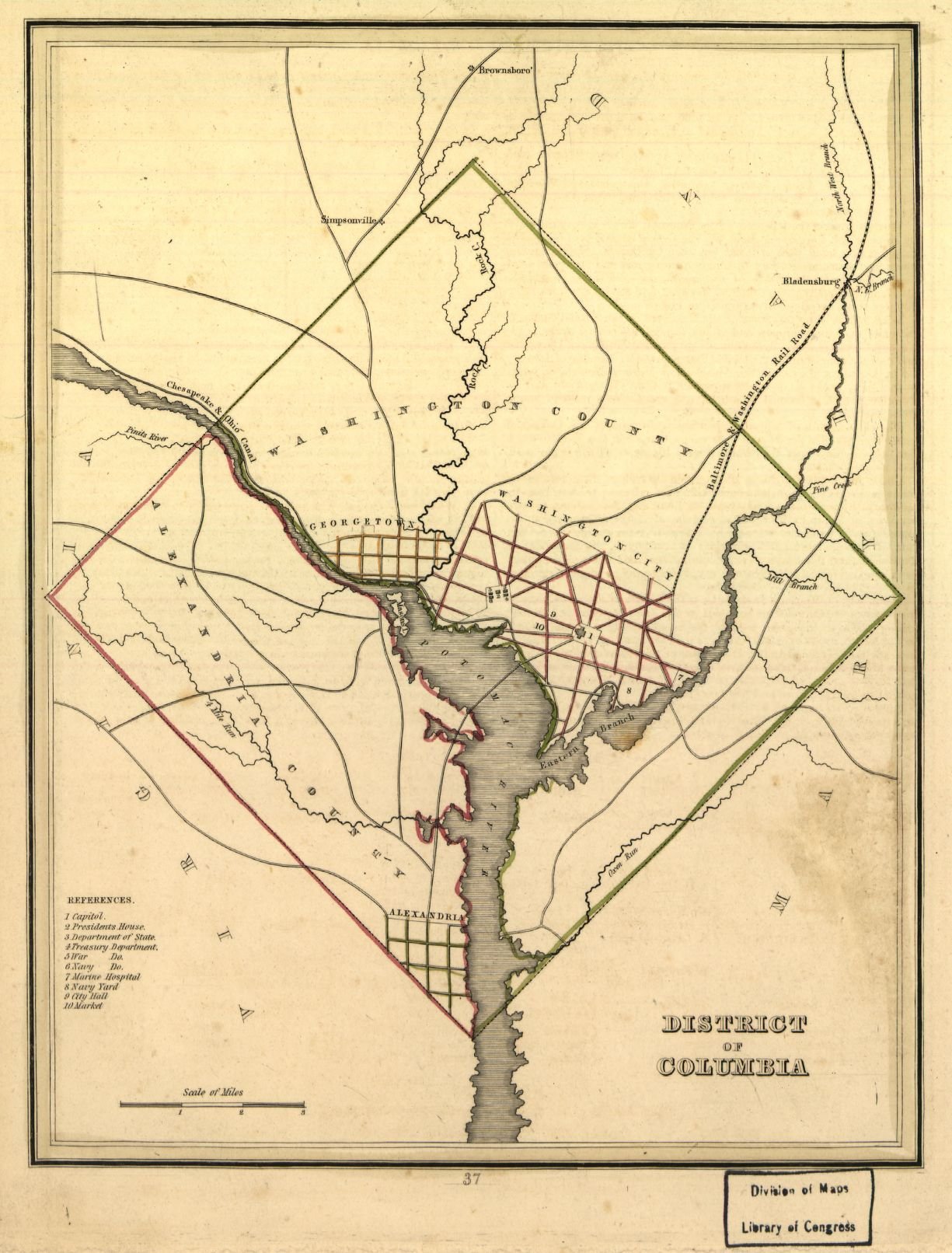

In the 1790s, Maryland and Virginia each ceded land to create a square that was 10 miles long on each side. Within it, the towns of Alexandria in Virginia and Georgetown in Maryland already existed. A new federal enclave with a building for Congress and the Supreme Court, the President’s House, and offices for the few federal agencies that existed were constructed. The first president to live in Washington was the second president, John Adams.

Map from 1835.

Alexandria’s city leaders thought they saw a good deal. The first of 40 boundary stones marking the District was placed at Jones Point, just below the city of Alexandria on the Potomac River, on April 21, 1791. A blessing by Rev. James Muir contained the following well-meaning thought:

Under this stone, may jealously and selfishness be forever buried.

Enthusiasm among Alexandria’s elite waned over the next few decades for a number of reasons:

Figuring-out pains: How would this new entity be governed? Who would try crimes? Which laws would prevail? Surprise—no one in Congress who passed the legislation thought this through.

Commercial disincentives: The law that established the District stipulated that no federal buildings would be built on the Alexandria side of the Potomac. So much for the gravy train. Construction of the C&O Canal diverted interior trade away from Alexandria.

Political power: Alexandrians realized that as part of the District of Columbia, they had no national representation.

Slavery: By the time the retrocession movement gained support, there was some movement to restrict slavery in the District. (The 1850 ban on slave-trading, often circumvented, was the only result).

Retrocession required approval by the Virginia General Assembly, U.S. Congress, and Alexandria voters. The local election took place September 2, 1846, with a resounding pro-retrocession victory (763 to 222).

Supporters paraded through the streets, marching around a huge bonfire and making merry. A song composed for the event included the chorus:

Hurrah! We’ll retrocede.

Alexandria Gazette, Sept. 2, 1846

For freemen’s lives we are bound to lead,

And to Virginia retrocede…

The happy crowd did not see the irony in celebrating that retrocession meant freedom. The Black population certainly did. Moses Hepburn, a free Black businessman, wrote northern abolitionist Gerritt Smith that as a running tally of the retrocession vote was announced from the courthouse steps, Black Alexandrians waited anxiously:

The suppressed wailings and lamentations of the people of color were constantly ascending to God for help and succor in this their hour of need.

They could not vote, but they had to bear the consequences of the lopsided approval.

The laws and practices in the District for a Black man, woman, or child were difficult enough, and, indeed, some of Virginia’s laws applied to Alexandria pre-retrocession. But retrocession to Virginia removed Alexandria from any Congressional oversight, stepped up enforcement of existing laws (such as a ban on Black schools), and introduced new restrictions.

A Term Used Today?

I fashioned the poster with the 1840s in mind. A few people, who had seen the title in the program, came over to see if I advocated retroceding the District of Columbia back to Maryland. Most definitely not.

D.C. Statehood, Long Overdue!