A Conversation with Meg Groeling, Author of First Fallen: The Life of Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, the North’s First Civil War Hero

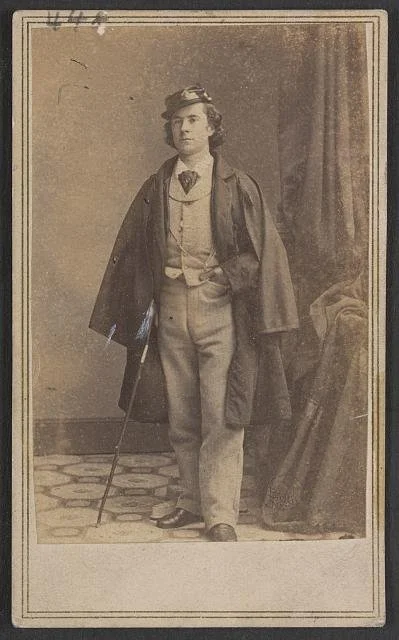

/“Remember Ellsworth!” screamed the headlines in Northern newspapers in late May and early June 1861. Colonel Elmer Ellsworth was killed at the Marshall House Hotel in Alexandria on May 24, 1861, one of the first casualties of the Civil War. The death of this 24-year-old “self-made man,” a friend of the Lincoln family and a media darling, took on outsized meaning across the North.

I recently had a great conversation with biographer and historian Meg Groeling about Ellsworth and his world. First, basic background:

Ellsworth’s “kepi” (hat) and other artifacts on display at Fort Ward Museum.

Elmer Ellsworth was born in 1837 in upstate New York. In 1854, he moved to Chicago to seek his fortune, where he met a former Zouave, a French Foreign Legion-type unit that gained fame in the Crimean War. After Ellsworth learned and excelled at the complicated Zouaves’ marching and acrobatic maneuvers, he trained a group of his contemporaries to become a Zouave unit. They performed in Illinois and then went on to a wildly successful tour of 20 cities. Ellsworth also caught the attention of Abraham Lincoln. He traveled to Washington with the Lincolns; when Lincoln called for volunteer troops in April 1861, Ellsworth went to New York City and formed Zouave-inspired unit (uniforms and all). After Virginia formally seceded from the United States on May 23, 1861, his unit was one of the first sent into Alexandria. There, he dramatically cut down an enormous Confederate flag flying atop a hotel called the Marshall House. Both he and the hotelkeeper/flag-bearer were killed in the ensuing melee.

That short chronology does not do justice to Ellsworth’s short, eventful life. Here is a bit more context from Meg, Better yet, read her book!

First Fallen, by Meg Groeling (Savas Beatie, 2021)

Q: How would you fit Elmer Ellsworth into the world around him?

A: He was sort of a nobody, which was one of the reasons I thought it was important to write the biography. I looked at young Yankee men like Ellsworth, and I began to realize they were, in fact, a unique set of individuals. They came of age at a time when, for the first time, it was possible for them to leave home—a family store, a farm—to start a whole new life. They could be their own men, “self-made men.”

I chose Elmer Ellsworth as my lens into the Civil War because he was part of that movement. The more I looked at these young men—many of whom would die in the next year or so—the more I became interested in the time period immediately before the war. The United States dis-united. Things happened that had never happened before. As I was reading the secondary sources, I started to think, Why in a year’s time, would men be willing to give up everything, put on a uniform, and go kill people? That’s a big ask. That’s when I realized being in a militia, like Ellsworth was in, was a big part of that.

Q: Ellsworth had a fateful encounter with Charles DeVilliers, a former French Zouave and now somehow a fencing instructor in Chicago.

A: Ellsworth was apparently really coordinated, physically and athletically. As a young boy, he was fascinated with soldiers. He was working out at the Y. Right into his lap falls DeVilliers, a fencing instructor. DeVilliers served with the Zouaves in the Crimea as a member of their medical corps. The Zouaves were an elite group. Ellsworth was all over that.

Ellsworth took fencing lessons and soon could do all the moves faster than DeVilliers. Together, they developed new moves, including one that they called the Lightning Drill. [To see versions of Zouave uniforms and drills, check out this clip from a 1953 Ed Sullivan segment on YouTube.]

Q: So Ellsworth trained a unit of Zouaves and took them on the road.

A: They performed in 20 cities across the North. When they came to a railroad station or if they came by boat, they were met by all these women just swooning, handing them bouquets and letters. They were hugely popular in New York City. It was like the Beatles came to town. Thousands of people saw them and it made Elmer Ellsworth a celebrity.

Q: It all happened so fast. The tour was in early 1860, and a few months later, he is a part of Lincoln’s inner circle when he runs for president.

A: That year was so incredibly important to him, to Lincoln, and to the country. All the things you read about Lincoln, right in the middle was Elmer Ellsworth.

Q: He goes to Washington with the Lincolns. Then, a few days after Lincoln calls for volunteer troops to fight, Ellsworth went to New York City and recruited one thousand fire fighters to become a Zouave-inspired regiment. How could a 24-year-old even do that?

A: He went up to New York with a letter from Abraham Lincoln to Horace Greeley [editor of the New York Tribune] that said, This guy is legit, help him out--of course, in more Lincolnian words. Greeley read it, looked over his glasses, and said, What do you need? He offered the Tribune presses to print recruitment posters. Ellsworth got introduced to everybody who was anybody. He had a real knack for meeting important people and making a good impression. He always got to the head of the line. He always had a sense of urgency.

He already had the plan to form the regiment from the Fire Department. Like everybody, he thought there would be one big battle and the conflict would be settled, and he wanted people who were trained to fight. Fire fighters weren’t necessarily trained to fight but they were trained to work as a group and as individuals. They used all kinds of athlete maneuvers to get to the tops of buildings and all that kind of stuff. He wanted young men in good condition, used to taking orders.

He went around to the fire stations and introduced himself. He signed so many people up, the mayor told him he had to stop so there would be fire fighters left to fight fires. He was limited to one regiment, which he raised in less than a week. He could easily have raised two.

Q: I’ve always wondered whether he planned to come to Alexandria deliberately to cut down the flag, or whether it was a split-second decision or serendipity once he got here.

A: I think it was serendipity. You have to remember, he was really just a kid, but he is carrying a ton of responsibility. He got his men to the capital from New York. There were problems, not just with his group—a lot of these guys were away from home for the first time, there was a lot of alcohol, there were women. The New York Zouaves were one of the most famous regiments and they received a lot of attention, good and bad.

The Marshall House was on the corner of King and Royal Streets, site of the current Alexandrian Hotel.

Ellsworth begs his commanding officer to allow his regiment to be in the first group to go over to Alexandria. He was headed to the telegraph office, as ordered, but I think he was seized by the moment when he saw the flag on the Marshall House.

Q: Talk about the impact of when he and James Jackson, the hotelkeeper, were killed.

A: I think this is really interesting. They got Ellsworth’s body out of the Marshall House hotel and back to the Navy Yard in Washington. His coat, which is at the New York Military Museum, shows a big hole right where his heart would have been, but his face wasn’t disfigured. He had an open casket funeral. The North was just convulsed that they lost their darling like this.

Jackson was well known in Alexandria. He was an ardent secessionist. He was bright, good looking, hard working. Any other circumstance, Ellsworth and Jackson would have liked each other. Jackson’s body was left for a couple of days, it was considered sort of a crime scene. He was embalmed and taken to his mother’s house in Fairfax County. There was a procession, but not like Ellsworth’s. He was in the Southern newspapers, but only for a few days. A book about him was written by a friend of the family the next year.

Two men died, we can’t forget that.

Harper’s depicted the Marshall House, the shooting of Ellsworth by Jackson, and the shooting of Jackson by Corp. Francis Brownell.

Q: What were some of your research “a-ha” experiences along the way?

A: I had some wonderful ones. Here are two that moved me the most. In 2011, when I was a year or two into the project, the National Portrait Gallery did a whole exhibit on Ellsworth. In the halls surrounded by Elmer Ellsworth, I was suddenly overcome. He became so real to me. I felt for the first time that he was real, and I was doing the work of a historian. I sat down on a bench and started crying. One of the wonderful guides came over and said, Are you all right. I blurted out what I was doing. Out of his coat pocket, he took out a cloth handkerchief and handed it to me. I still have it. He recognized how important this was to me.

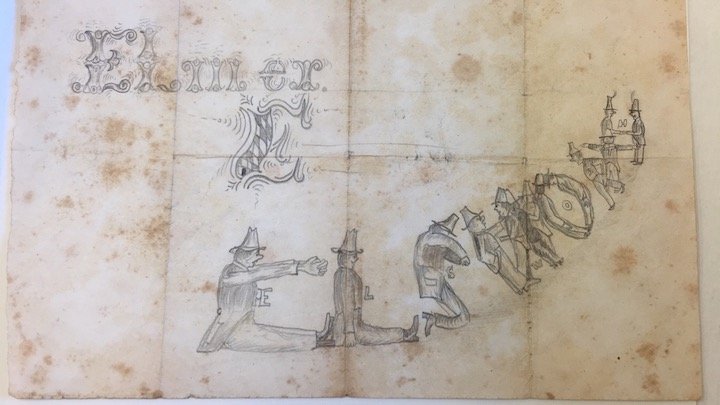

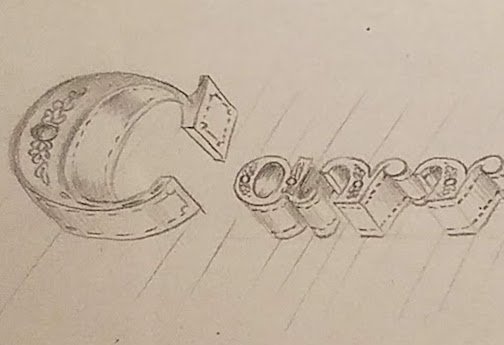

The other one--In a lot of his notebooks and letters, he doodled. Early on, I found his writing of his name, with each letter a picture of a soldier. It was almost childish silliness. Then I got to the Kenosha Civil War Museum, an amazing museum that concentrates on Wisconsin’s and Illinois’ contributions to the Civil War. I was looking at the exhibit cases, and there was one of Ellsworth’s notebooks. In it was his depiction of Carrie’s name [Ellsworth fiancé Caroline Spafford], drawn with vines and flowers.

Then I opened a scrapbook inside one of Carrie’s boxes in the archives. She had cut out all the newspaper clippings about him. Suddenly there was a double-paged spread with articles about him lying in state in New York City and Utica. Lying in between the pages was a sprig of pressed flowers and leaves. She could not attend the funeral. Someone had clipped and sent them to her. I was awe-stuck. That was when Carrie came real to me. She was 18, her fiancé was dead. He was a public figure but she was privately grieving.

He was a very young man, still at the point where he was drawing names in soldiers and flowers. You realize these people lived, they were real people, representative of the many women whose men didn’t come home and the many soldiers who themselves did not come home.

Meg Groeling. Credit: Noella Vigeant Photography

ABOUT MEG:

Meg Groeling’s book, First Fallen: The Life of Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, the North’s First Civil War Hero, was published by Savas Beatie in December 2021. Order it here.

Always interested in the Civil War, she was fated to write this biography when she taught at E.E. [Elmer Ellsworth} Brownell Middle School in California.

She also regularly writes for the Emerging Civil War blog.