Writing a Book Review of The Last King of America

/I write the occasional book review for the Washington Independent Review of Books, usually histories or biographies. One reason i like doing it is that it helps my own writing to really read a book—what works and what doesn’t, what I liked and why, how can I learn from the content and/or the craftsmanship to improve my own work-in-progress.

I’l admit that I gulped when my recent assignment came in the mail—almost 800 pages! Not to mention, the subject was George III, the King of England who reigned at the time of the American Revolution. As more of a 19th-century U.S. than an 18th-century British gal (although George III did live until 1830), I am definitely not as well versed in the historical context.

The cover copy for the U.S version promises American readers a way to see who the real George III was, rather than the impression of the silly king from the play Hamilton. That is a bit of a marketing ploy, because (as I wrote in the review) this “massive and meticulous biography” extends far before and far beyond, both time-wise and location-swise, our 13-colonies lens.

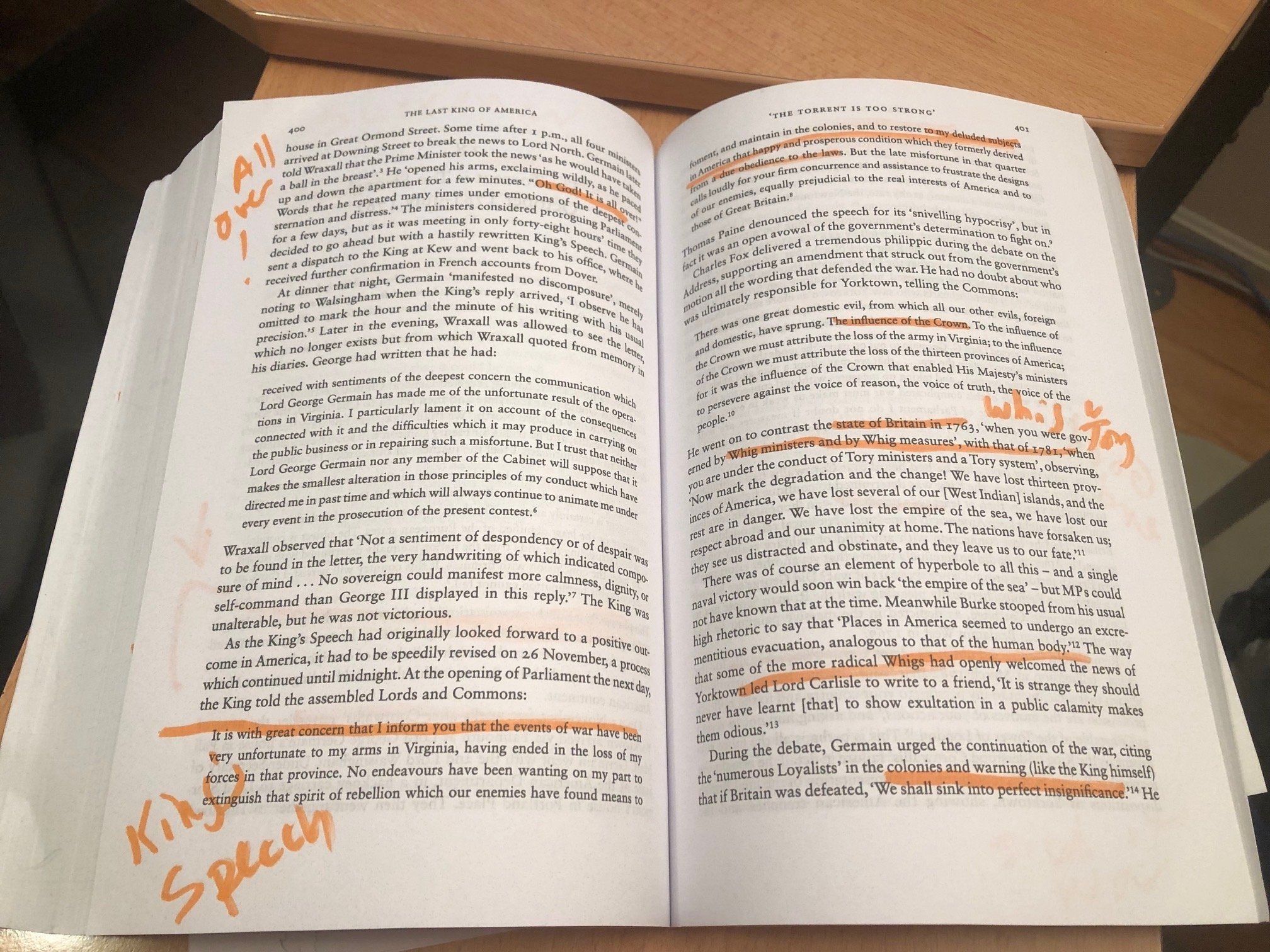

And because it was an “advance uncorrected proof,” it had no index. I made liberal use of an orange highlighter to orient me when I went back into the book to write my review.

To fellow writers, I’d also like to share an anecdote before I get to the review itself. My deadline was the end of October 2021, and I sent it in around the 23rd. I didn’t hear anything but figured the editors would get to it….or maybe the draft was horrible…or maybe they decided not to review the book….or? (yep, writer’s insecurity). Last week, the editor emailed to ask about its status. Yikes! She had never received it and thought I missed my deadline (one thing I can truthfully say is that I never miss a deadline). I re-sent it immediately and it ran with only a few small edits on December 7. So when you have submitted an article or a story and you don’t hear—it might not be because your piece was rejected!

So, my review of The Last King of England: as first published in the Washington Independent Review of Books: The Misunderstood Reign of George III by Andrew Roberts begins below (or you can read it on the WIRoB site):

“He’s hardly the bumbling, rapping monarch from “Hamilton.””

Historian Andrew Roberts urges us not to think of actor Jonathan Groff’s exaggerated portrayal of George III in the musical “Hamilton” when judging the monarch who was, indeed, America’s last king. Of course, given that warning, anyone who has seen the production immediately conjures up a silly, sputtering ruler who embodied all that our Founding Fathers revolted against.

Aided by the opening of the Georgian Papers in Britain’s Royal Archives, Roberts states a primary aim of his massive and meticulous The Last King of America is to dispel this image for American readers. He depicts instead a thoughtful, serious ruler who, as the subtitle suggests, was misunderstood not only by his former subjects in the colonies, but also by just about everyone else around him.

George III was born in 1738, became king in 1760, and died in 1820. Although mental illness incapacitated him, especially in the last 10 years of his life, he is Britain’s longest-serving king, surpassed only by Queens Victoria and Elizabeth II. At just 22, he ascended to the throne — well educated by a private tutor, devoutly religious, rule-bound, and fiscally conservative. He had no friends his age and strongly disapproved of the pleasure-seeking shenanigans that characterized upper-class society. Fortunately, an arranged marriage with Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, whom he met for the first time on their wedding day, was a happy one.

(For those tracking popular-cultural references, this would be the queen in the Netflix series “Bridgerton”; Roberts does not agree with the assertion by some historians that she was biracial.)

His coronation took place during what we Americans know as the French and Indian War; its name in England — the Seven Years’ War — more accurately reflects the conflict’s complicated global nature. According to Roberts, Britain’s victory in that war in 1763 paved the way for the American Revolution. Rather than grasp that the removal of the French threat and explosive population growth in America required a recalculated relationship across the Atlantic, the king and other leaders assumed the colonists would remain satisfied with the status quo. Roberts conjectures what might have happened had they been more foresighted.

Although George III could freely share his views with politicians, Parliament governed the realm. Thus, Roberts says, Parliament was the real opposition to American aspirations. This is not to say that the conservative and tradition-bound king would have championed American independence. But Roberts points out that the Americans’ attacks on the tyranny of the king, framed most notably in the Declaration of Independence, were misplaced.

Several chapters present events leading up to and during the Revolutionary War from a British perspective: the Boston Tea Party, tax acts, and Yorktown, to name a few. And while we are taught how Americans fought as military underdogs, Roberts shows the British, in fact, doomed their own effort “by refusing to change their basic military doctrine and almost anything fundamental at home, in terms of finances, commercial arrangements, conscription and tax levels.” George III saw much of this, Roberts says, but could not alter the course of events.

George III was both intellectually curious and curiously close-minded. Passionate about the arts and scientific discovery, he never traveled to America or even Ireland or the industrializing north of England. Granted, travel at the time was neither comfortable nor easy, but Roberts speculates whether firsthand observation might have affected how he addressed the huge changes taking place in his realm.

Roberts also describes the heartbreaking mental illness that afflicted George III on several occasions, beginning in 1765. The attempted cures — leeches, cupping, and other painful and ineffective treatments — almost killed him. He had lucid moments in which he was aware that he would sink back into madness yet could do nothing to prevent it. Meanwhile, his luxury-loving eldest son was champing at the bit to have his father declared incompetent. George III lived the last decade of his life virtually alone while his son ruled during the period known as the Regency.

For American readers drawn to this biography by Roberts’ promise to set the post-“Hamilton” record straight, it’s important to remember that the Revolution occurred less than halfway through George III’s reign. The book goes far beyond that period, as it should. Expect a lot of detail about parliamentary machinations among various Whigs and Tories, with the author’s judgments about who among them did and did not serve Britain well. As it happens, Roberts also aims to counter British misconceptions about their king. Indeed, the title of the book’s British version is George III: The Life and Reign of Britain’s Most Misunderstood Monarch.

Among Roberts’ previous work are books on military history and a biography of Napoleon. He draws on this background to place George III in the context of his times and to explain British military strategy. “Oceans rise, empires fall” sings George III to America in “Hamilton.” Reading Andrew Roberts’ authoritative The Last King of America, it’s clear that George III had a lot more to contend with than a bunch of rambunctious, rapping colonists.

NEXT UP: Review of a book due out in March 2022: The Turning Point: 1851—A Year that Changed Charles Dickens and the World by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst.

Paula Tarnapol Whitacre is a writer, editor, and biographer focusing on 19th-century social history. She holds undergraduate and graduate degrees in international studies, with a concentration in American foreign policy, from the Johns Hopkins University.