Harriet Jacobs in Edenton, North Carolina

/A weekend trip for a history geek (and her patient spouse): We went to Edenton, NC, the birthplace of Harriet Jacobs; the Great Dismal Swamp across the NC-Virginia border, where many people escaping slavery hid; and Fort Monroe. where three men escaping slavery were defined as “contraband” to avoid their return to the slaveholder.

But the main activity was a Harriet Jacobs walking tour, conducted by Historic Edenton. (They run these tours periodically for a nominal fee. along with other exhibits and events.)

Geography

Edenton is billed as one of “America’s prettiest towns” and it is, indeed, lovely. It was North Carolina’s first capital in the early 1700s and a busy seaport on the Albemarle Sound. Natural and human-made changes to the waterways made it less viable and commerce dropped, but it still had some shipping. Today, it has a beautiful waterfront park and pier at the end of the main street.

Many landmarks connected with Harriet Jacobs’s life no longer stand, but their locations are known. Other period homes and public buildings can help conjure up life in pre-Civil War Edenton.

Biography

For those not familiar with the life of Harriet Jacobs, this very brief synopsis does not do justice. Her own story—captured in her narrative Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl—and a 2004 biography by Jean Fagan Yellin (Harriet Jacobs: A Life) provide much more information.

To set the stage for the Edenton landmarks, however, Jacobs was born into slavery in 1813. In her first few years, she lived first with her mother, then with a slaveholder who taught her to read. But when the woman died, Harriet was bequeathed in a rather murky will to her niece, 3-year-old Mary Matilda Norcom. and thus entered the household of Dr. James Norcom.

Norcom was a controlling, would-be rapist. Jacobs held him off by entering into a relationship with a more prominent white man in the town named Samuel Sawyer. (The calculus of this decision is painful and laid out in greater detail in the books above.) She had two children with Sawyer, a son and a daughter, who were legally owned by the Norcoms. In 1835, she decided to escape. Her hope: Sawyer would then purchase and emancipate her children.

The escape plan was to find a sea captain who would take her north for a price. In the meantime, she hid in the attic of the home of her grandmother, Molly Horniblow, who had purchased her own freedom in 1828. It took almost 7 years to find the escape; she remained secretly in this confined space all that time. In 1842, she finally left.

No known images of Harriet Jacobs exist from this time. An advertisement taken out by Norcom, seeking her capture, provides a verbal description, albeit through his racist lens.

Harriet Jacobs was in her grandmother’s attic nearby when Norcom placed this ad in a Norfolk newspaper.

Tour and Texts

Our walking tour left from the visitors center and went by location, of necessity skipping around her life. I have rearranged the stops to go more chronologically, also quoting a relevant excerpt from her book.

First, the overall lay of the land. The map on the left (from a signboard) shows the larger area. The one on the right focuses on downtown and our walking tour. Even without knowing which site is which, it is clear how close together everything was in Edenton.

Horniblow Tavern

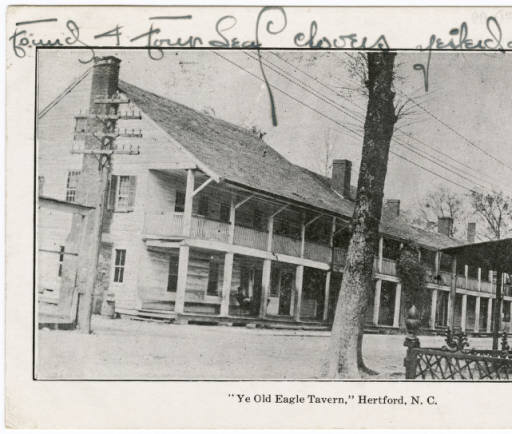

Harriet’s grandmother’s last name was Horniblow, because that was the surname of her slaveholders, who ran a successful hotel and tavern. Grandmother Molly, her daughter Delilah, and Delilah’s children Harriet and John lived on the premises in Harriet’s earliest days. Image on the left is a tavern in nearby Hertford, perhaps evocative of Horniblow’s Tavern. (The postcard is from North Carolina Postcards, an archive at UNC-Chapel Hill.) The photo on the right shows the site today, a 1926-era hotel in need of some TLC.

From Incidents:

She [Harriet’s grandmother Molly] was a little girl when she was captured and sold to the keeper of a large hotel….She became an indispensable personage in the household, officiating in all capacities, from cook and wet nurse to seamstress.

Molly put her baking skills to work and sold products on her own (permission needed to be granted for this). She saved to purchase her and her children’s freedom but was only able to emancipate herself and one of her sons. Her other children were “divided up” in post-death settlements, and the Horniblows also took most of her savings.

Molly Horniblow’s House and Shop

Shared by our tour leader from Historic Edenton.

As testament to what an amazing woman she must have been, Molly purchased the building where she lived and operated a bakery. This put her in rare company as a free African American female property owner, and not surprisingly, she was a major influence on Harriet’s life. She also commanded respect in the community, especially considering her status as a woman of color.

This drawing, shared by our walking group leader, is believed to be what the property looked like. It is now the back of a building and parking lot.

From Harriet Jacobs: A Life:

Her free papers issued, Molly moved into Gatlin’s [Albert Gatlin, a white lawyer who helped secure her freedom] empty house on King Street, opened a bakery….John [Harriet’s brother] later explained that Gatlin sold her his house…

From Incidents:

My grandmother had, as much as possible, been a mother to her orphan grandchildren. By perseverance and unwearied industry, she was now mistress of a snug little home, surrounded with the necessities of life.

The fact that Molly owned her own home was critical to the future of Harriet and of Harriet’s children, Joseph and Louisa.

Norcom Residence

At age 12, Harriet went from a relatively easy life with an infirmed white woman to the Norcom household.

The house is now the parking lot of the Edenton Baptist Church. His medical office was a few blocks away on the corner of King and Broad streets. Thus, as the map showed, everyone lived very close to each other.

From Incidents:

When we entered our new home [the Norcom residence] we encountered cold looks, cold words and cold treatment.

Things became worse, once Dr. Norcom set his sights on Harriet:

I now entered by fifteenth year—a sad epoch in the life of a slave girl. My master began to whisper foul words in my ear….He tried his utmost to corrupt the pure principles my grandmother had instilled….I turned from his with disgust and hatred. But he was my master. I was compelled to live under the same roof with hime—where I saw a man forty years my senior violating the most sacred commandments of nature.

Harriet fell in love with a free black man—but had absolutely no possibility of sustaining a relationship with him. She had to turn him away. She did not write about another romantic encounter in her life.

But she did have another relationship, this one with Samuel Sawyer, a more elite, younger, and somewhat more palatable white man than lecherous Norcom. The relationship kept her out of Norcom’s sexual clutches, and produced her two children to whom she dedicated her life.

St. Paul’s Church

Harriet christened her children at St. Paul’s when Norcom was out of town. Molly was a member (at this time, blacks and whites both worshipped there, albeit with the blacks in a second-class situation). Harriet deliberately chose her children’s (and ultimately her own) surname. They could not take “Sawyer” for obvious reasons, and she refused to honor the names Norcom or Horniblow. “Jacobs” was her father’s last name, although she recognized the complexity with that choice.

From Incidents:

…I added the surname of my father, who had himself no legal right to it; for my grandfather on the paternal side was a white gentleman. What tangled skeins are the genealogies of slavery!

Norcom was a member of the church. When Harriet asked him about his turn toward religiosity, he said his position in society required it. Jacobs had choice words about the hypocrisy of religion in the slave-holding south. Norcom, who died in 1850, is buried in the church cemetery, with a tall obellsk of remembrance. The monument reads, “One of the most distinguished physicians in the state.”

Attic Hideout

Norcom decided to extract Jacobs out of Edenton, away from her support systems, and to “break” her children in as slaves. She was about 22 years old when he moved her to a plantation run by his son. One late night, she slipped away and returned to Edenton. Friends hid her for a few days, then she went into the nearby swamp. Meanwhile, her family was trying to arrange safe passage for her out of Edenton. Her uncle built a small space in Molly’s attic as a holding place.

The space was 9 feet by 7 by 3 feet tall. We laid out string on the ground to show how small that area is. It had no heat or insulation, and she shared the space with vermin and rodents. Sawyer eventually purchased her children from Norcom (but did not emancipate them), and they lived downstairs. They were not told their mother hid upstairs to protect the secret.

Andrew, the tour leader, and Bill, my husband, lay out a 9 by 7 foot area, the size of Harriet Jacobs’ “home” for almost 7 years. it was across King Street, where the small parking lot is now located.

It took almost 7 years to find a way out for Harriet Jacobs. Norcom never knew that he passed by Harriet Jacobs multiple times a day.

Jail for Her Family

One impediment to people escaping slavery was the justifiable fear that family members left behind would suffer. Sure enough, Norcom imprisoned her children, brother, and aunt for several months in hopes that someone would reveal Harriet’s whereabouts.

From Incidents:

When I heard that my little ones were in a loathsome jail, my first impulse was to go to them.

But her family convinced her that revealing herself would harm everyone, including the people who protected her, and she hung tight.

Her aunt, also enslaved in the Norcom household, was let go after Mrs. Norcom complained about the lack of her housemaid. Imprisoning a 2 and 6 year old finally seemed absurd . Through a series of ruses, Samuel Sawyer purchased them from the Norcoms.

The jail looks like an unpleasant place to spend any time at all. It was used, we were told, until 1975.

Escape

In 1842, a ship captain was found (his identity remains unknown). As Harriet and her family debated the wisdom of her leaving, another enslaved woman saw her. They did not entirely trust her, so the decision was made to seize the offer—and fortunately worked out successfully. As they finally got out to sea, she felt fresh air for the first time in years.

From Incidents:

I shall never forget that night. The balmy air of spring was so refreshing! And how shall I describe my sensations when we were fairly sailing on the Chesapeake Bay?

It took 10 days to reach Philadelphia. Her freedom remained precarious, but she was out of slavery for good.

And so our tour ended, late along the waterfront on a November afternoon as the sun set and it turned cold. As always, seeing a place made a huge difference in my appreciation of and respect for Harriet Jacobs.