Susan Ireland's Boarding House on Seventh Street

/On the panel, July 13, 20017, Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office (probably should have brushed my hair one more time)

The June issue of the Surgeon's Call, the magazine of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, includes my article on the the building that now houses the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers' Office on Seventh Street NW (unfortunately, print only). Last night, I took part in a panel at the "CBMSO" (run by the Civil War Medicine museum) to talk about "Clara Barton's associates." In my case, the "associate" was the building's owner, Susan Fowler Ireland.

Here's what I said, lightly edited:

We don’t have any record that Susan Fowler Ireland and Clara Barton were “associates,” or in fact if they met in person or how they interacted.

But if it weren’t for Susan Ireland, we might not be sitting here tonight.

Ireland bought this building as an investment in 1857. We are not sure the exact purchase price, but she paid taxes on an assessed value of $9,200 in 1859. Shops occupied the first floor, with offices on the second floor. On this floor, boarders like Clara Barton rented rooms for months, or even years at a time.

I became interested in boarding-house life when I researched the life of Julia Wilbur, an abolitionist who taught school in Rochester, New York, worked as a relief agent during the Civil War in Alexandria, and then worked in the Freedmen’s Bureau and Patent Office here in Washington until her death in 1895. She and Clara Barton are what we would call “social acquaintances," especially in the 1870s and 1880s.

Along the way, she lived in a series of boarding houses, including several in this neighborhood. She wasn’t alone. According to historian Wendy Gamber, in the 1800s, anywhere from 1/3 to ½ of urban America lived in, or ran, a boarding house.

Boarding houses allowed people like Julia Wilbur-- and Clara Barton--to move to cities for new opportunities and have a place to live. They could go beyond the confines of family. “Keeping” a boarding house also gave middle-class women a socially acceptable way to earn money. Many of them rented out rooms literally to keep a roof over their and their children’s heads.

So when I offered to do some research for the museum, I was excited when Terry said she wanted to learn more about the building as a boarding house and about the owner. She gave me Susan’s name and a few other bits of information. I pieced together some interesting parts of the puzzle in the past few months. Some other parts remain unknown, at least for now.

I am going to briefly highlight her life. Then I will focus on 2 things:

- First, my path from learning her name to locating her descendants to fill out her story

- Second, how her life was typical of, but also differed from, women in 19th century Washington.

A quick rundown begins in Prince George’s County. Susannah Fowler was born in 1788, one of 9 children. She married a man named James Ireland in 1806. At this point, we don’t have further information about him. But it seems they did not own land and did not have any living children. She was widowed in middle age.

What happens to a childless, middle-class, middle-aged widow in the 1800s? Many of them, including Susan Ireland, move in with other family members.

By the 1840s, she had come to Washington. In 1850, the Census records show she lived with Samuel and Jane Fowler, her nephew and niece, and their large family on F Street, across from what is now the Verizon Center.

Starting in the mid-1850s, Samuel and Susan joined with a few other people to form a private bank. This was an era known as the Free Banking Era, in which people could take in deposits, lend money, and the like, with little oversight or regulations. Clara Barton deposited some of the money to operate the Missing Soldiers Office in their bank, which was nearby on Pennsylvania Avenue.

Ireland was the only woman of 6 or so partners—always listed as “Mrs. Susan Ireland,” at the end of the list of men. But she was listed by name, publicly.

I found all this information in City Directories, the Evening Star, the Census, and other records.

But I was still struck with a question: How did she have the money to become a partner in a bank and purchase this building?

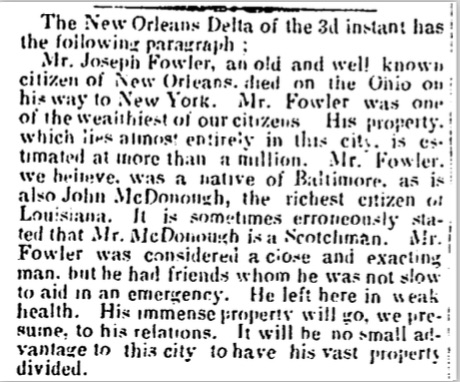

My break came through a site you may know if you do genealogy research—FindaGrave.com. I connected with the great-great-great grand-daughter of one of Susan’s brothers. She shared a “truth is stranger than fiction” story. Joseph Fowler, the youngest son in the family, moved to New Orleans, where he made his fortune. He died at sea in 1850, without a will or an immediate family as heirs. When he did, he left an estate of $1.48 million. After several years, including a case in a Louisiana court, his fortune was divided up among his three surviving siblings and the children of the siblings who had already died.

Susan Ireland received one-eighth of the total. She had a lot of money to invest.

coincidentally, news of Joseph Fowler's death APPEARED in the Alexandria Gazette on September 13, 1850.

Through the family connection, I also "met" another family member who owns the photo used on FindaGrave. As we corresponded for this project, one result is that he plans to donate the original to the CBMSO.

Finally--

Susan lived the respectable life of a white, wealthy widow in mid-nineteenth-century Washington. She donated to the Washington City Protestant Asylum for Orphan and Destitute Children during her life, and also bequeathed $8,000 to the asylum in her will.

Part of that existence meant that she owned two people, a man named Henry Hammond and a woman named Elizabeth Brent. In 1862, when slaves were emancipated in the District of Columbia, she petitioned for the compensation that the law allowed. To do this, she had to swear loyalty to the Union.

She was apparently a woman not hesitant about using her money to make more. In addition to this building and the bank, she owned at least one other property, and she lent money to more distant family members and at least one other property owner who lived near here. In each case, she had a deed of trust drawn up and earned interest. Samuel acted as her intermediary, but she is listed as the lender.

Susan Ireland died on April 10, 1869, at age 80. This building passed on to Samuel Fowler and, when he died, to his widow and Susan’s niece, Jane Fowler.

In her will, in addition to money to the asylum and to Samuel Fowler for his services as an executor, Susan Ireland divided her estate into 150 shares. She then parsed out the shares to at least 25 different family members. 5 shares to this nephew, 15 shares to that niece, and so on. She pointedly excluded several of them. And in the case of several of the young women, she noted the money was for their “sole and separate use,” to protect it from being usurped by their husbands or other male members of the family.

We do not have any of her letters or diaries to know her own voice. As I mentioned, we do not at this point have any records of interactions with Clara Barton, Edward Shaw, and other boarders. But we do have the photograph of a rather imposing woman, late in her life. She looks like a woman who knew her mind.

Susan Foster Ireland, Circa 1864, Original at Cole Camp Museum, copy on Findagrave.com