The Conspirators' Trial Began May 9, 1865

/Among the many "trials of the century," the trial of eight people charged with conspiracy to assassinate President Lincoln and other officials ranks high. The nation reeled. The man who pulled the trigger, John Wilkes Booth, was himself shot. The defendants most notably included Mary Surratt--the involvement of a woman in the crime itself cataclysmic.

As a reminder

- The assassination took place April 14, 1865; Lincoln died early the morning of the 15th.

- John Wilkes Booth was on the run in southern Maryland and the Northern Neck of Maryland until April 26.

- The arrests of the others occurred throughout the month.

- The trial (controversially, military rather than civilian) began at the Old Arsenal Penitentiary, now on Ft. McNair in Southwest Washington, on May 9.*

- The verdicts were handed down on June 29--all guilty.

- The hanging of 4 of the 8 took place on July 7.

Less than 3 months stretched between the assassination and the executions.

(Thanks to Dave Taylor, who blogs, gives talks, etc. about the conspiracy & aftermath--my original post said May 8, which was when the charges were presented to the defendants.)

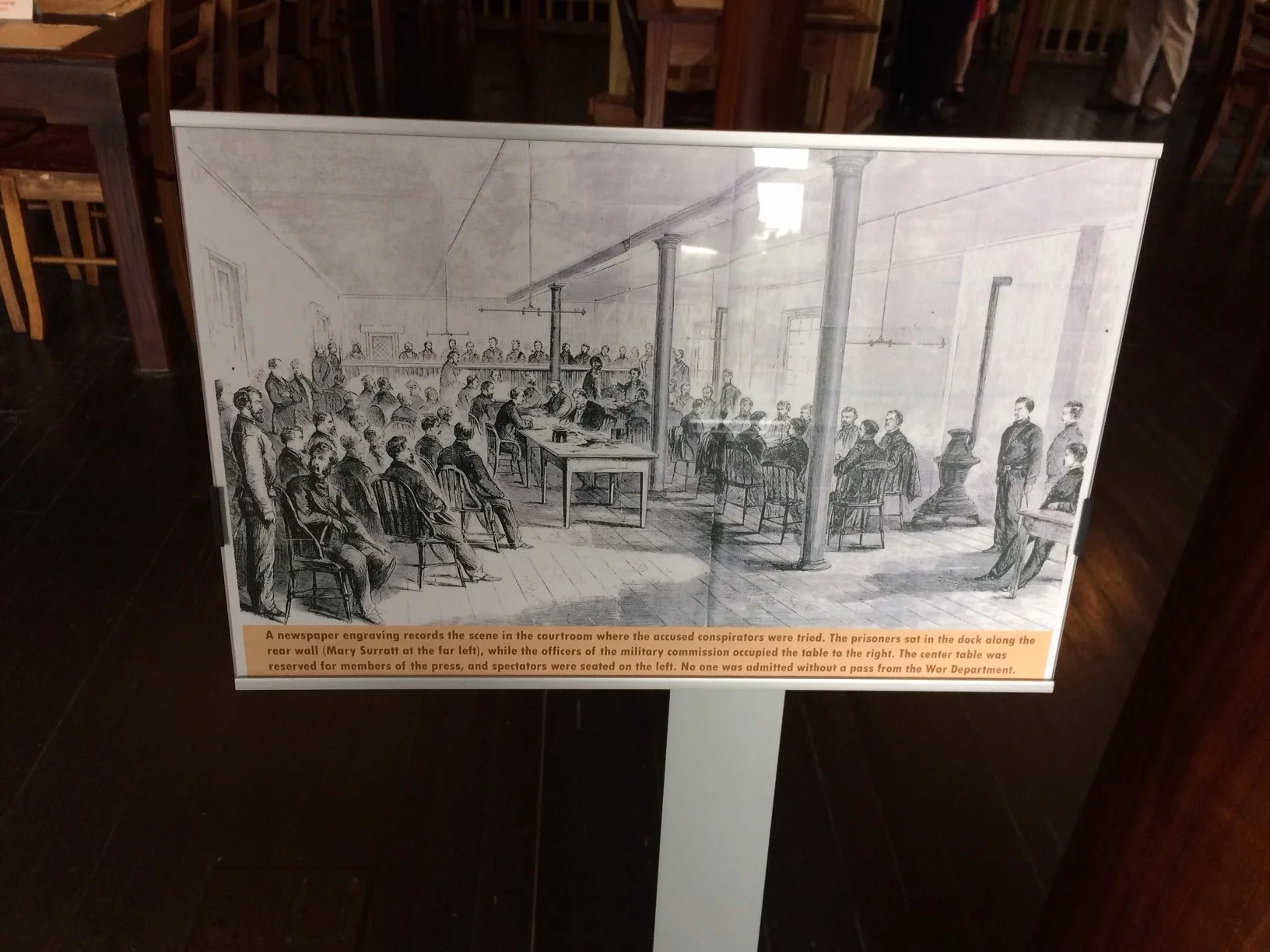

Visiting the Court Room: Then

The trial was open to the public, and a particular draw for Washington's society set. Visitors sat in one corner of the makeshift courtroom on the 3rd floor of the building, in sweltering heat. The three prosecutors and nine-member military commission sat together at one long table, with the witnesses and stenographers facing them. Up on a riser along the side, the 7 male defendants sat on a bench, with a guard in between each one. Surratt had a chair in the corner, usually draped in a black veil. Reporters, sitting at another long table toward the back of the room, produced voluminous amounts of copy every day.

The courtroom--although this drawing does not show, according to the Evening Star, "the many ladies, some of whom have been present nearly every day the trial has been in progress."

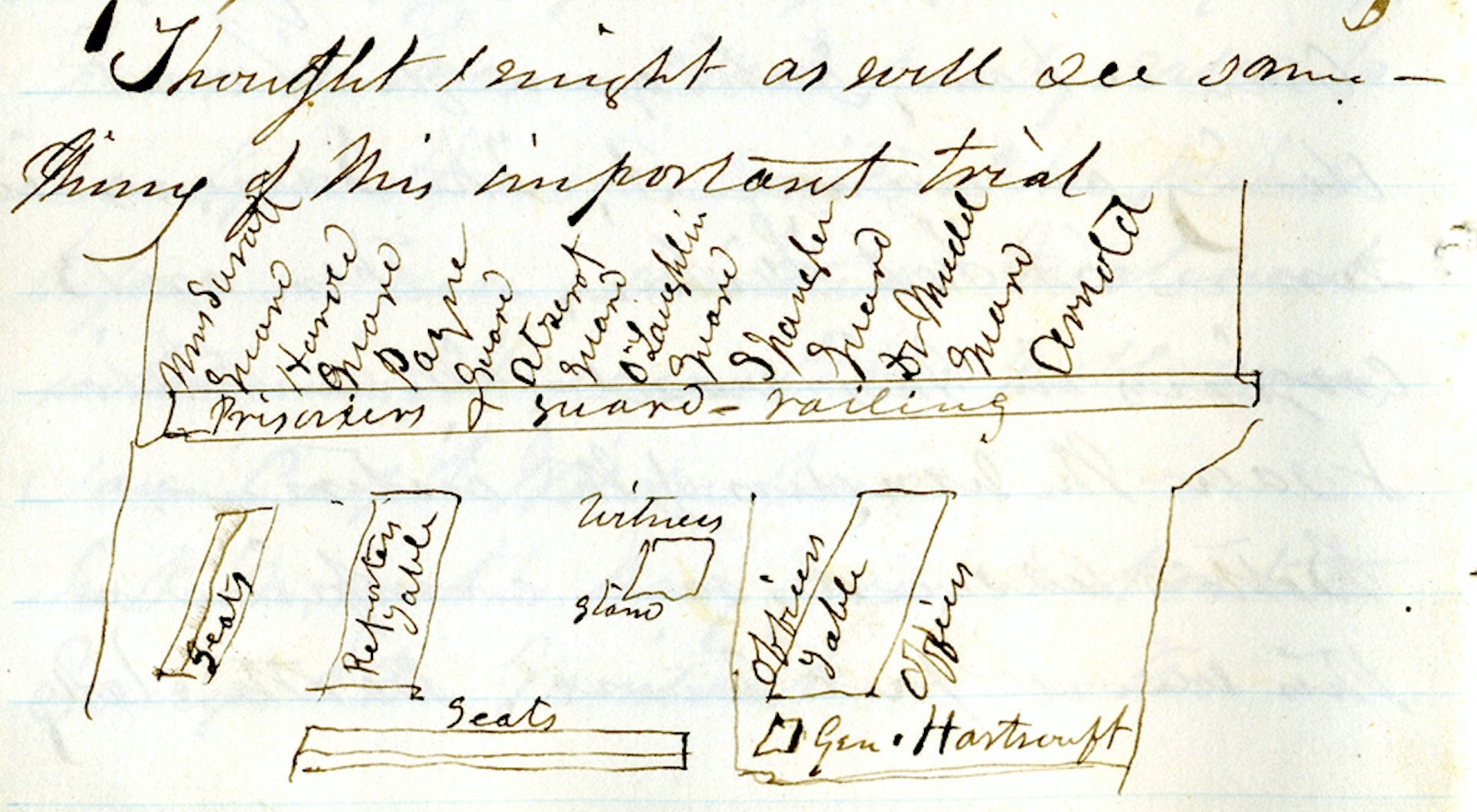

In addition to reading accounts of the trial (most recently, Assassin's Accomplice by Kate Clifford Larson), I had another guide: Julia Wilbur visited the courtroom on June 19, 1865, and sketched out two courtroom scenes.

In 50 years, she included fewer than a half-dozen drawings in her diaries. These were two of them!

"Thought I might see something of this important trial." In the drawing, Julia focused on the defendants (each separated by a guard) seated on a bench along one side of the room.

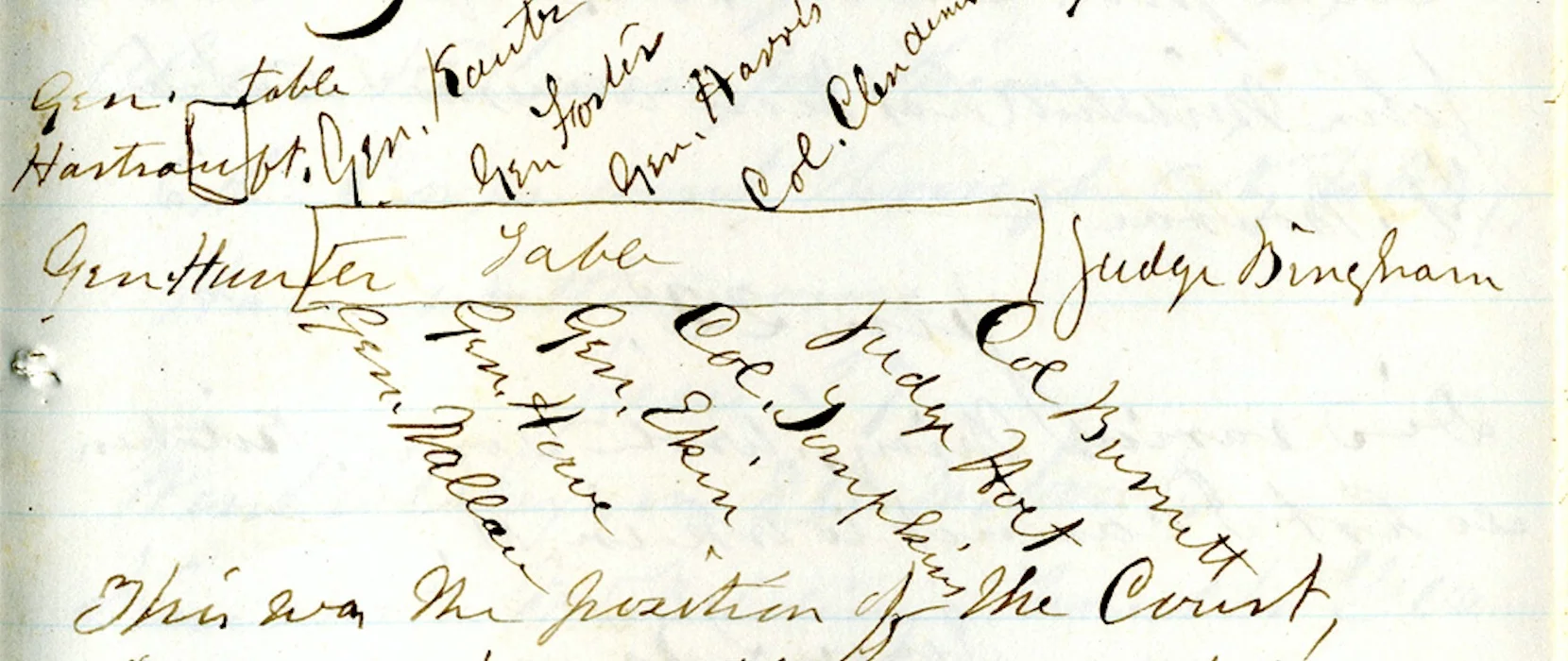

"This was the position of the court." This drawing is of the table (bottom right above) with the prosecutors and commission judges. They sat together, while the defense attorneys had chairs here & there in the courtroom.

Visiting the Court Room: Now

A few times a year, the room is open to the public--and I went this past Saturday. The hulking penitentiary was mostly torn down over the years, but the portion that contained the courtroom, now called Grant Hall, remained. A renovation in 2013 re-created it as used in 1865; originally, it was a hastily transformed assistant warden's office. The artifacts are re-creations used in the film The Conspirator.

I checked to see if the seating arrangements matched Julia's sketches. They did.

Yes, Julia's second drawing matches the names and placement of the prosecutors & commission at this table.

Julia's sketches, various written descriptions, and even the movie did not prepare me for the small, claustrophobic size of the room. (Two small rooms in the back, now with some exhibits, were also used as witnesses, defense attorneys, and others rotated in and out.) The witnesses faced the judges, and could not have eye contact with the defendants. The few small windows probably did not help much during the hot early summer days of the trial. One of the historians on hand for the open house noted that defendant Samuel Arnold had the best seat, next to a window, at the end of the bench.

The four defendants sentenced to death were executed right outside the room, along what is now a tennis court.

Should a military commission have tried the case? Did the defendants have a fair trial? Was Surratt guilty in the assassination conspiracy (versus an earlier, failed attempt to kidnap Lincoln)? Historians and others continue to debate these questions.